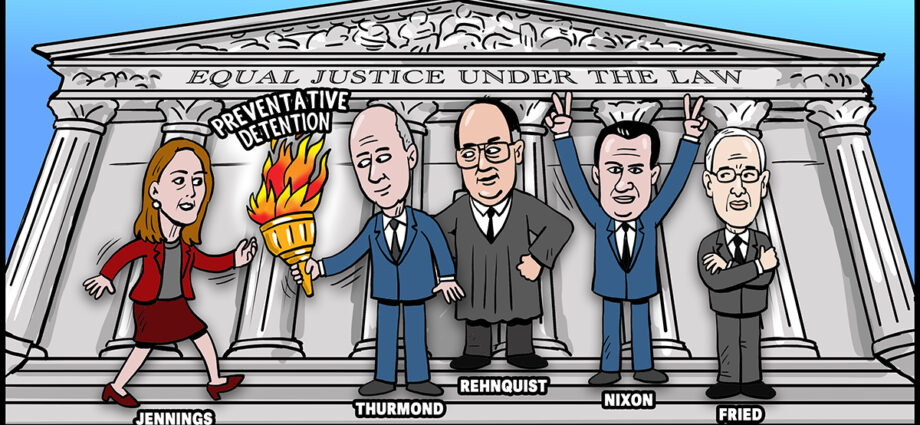

Will Delaware Attorney General Kathy Jennings be the First Lawyer in a Generation to Defend Segregationist Strom Thurmond’s Preventative Detention Law before the U.S. Supreme Court?

The short answer appears to be yes, as WHYY.org has reported that Delaware Attorney General Kathy Jennings supports the change to Delaware’s constitution, presumably meaning she has fully evaluated the same legally and is prepared to go to state and federal court to vigorously defend it.

Yet, as the constitutional fallout from Bruen continues on the other constitutional amendments, the original meaning of the 8thAmendment is back on the table. Because the Supreme Court has only interpreted the amendment once since 1951, and arguably in dicta, Stack v. Boyle, 342 U.S. 1 (1951), it is quite likely that the flimsy doctrine of preventative detention upon which the proposed Delaware constitutional amendment is legally based, like it or not, is sure to come back before the Supreme Court. In fact, the Delaware constitutional amendment is the precise vehicle opponents of preventative detention have been waiting for.

Speaking of the origins of preventative detention, allow us to explain the origins of this concept called preventative detention now that the Supreme Court applied the new standard in Bruen. Delaware Attorney General Jennings is now going to bear the burden of providing historical evidence pursuant to Bruen that preventative detention was an allowable power of the government in prosecuting a criminal defendant, that despite precisely zero textual or historical support.

So, where did we get preventative detention? The record is quite clear on that point. Richard Nixon ran for president on the idea that people who are a “clear and present danger” to society must be held in “pretrial preventative detention.” That term had no legal or other meaning when it first was uttered by then former Senator Nixon. The federal city was chosen to be the lab experiment with this new preventative detention statute, which was invented in 1969 by a defender of Plessy v. Ferguson, none other than Assistant Attorney General William H. Rehnquist, Jr. At the time, the panel of judges approving “pretrial preventative detention” in the District of Columbia split down the middle, 6-5, and the new statute passing by a mere single vote, likely under White House pressure. Interestingly, at AAG Rehnquist’s Senate confirmation hearings,[1] members of the Democratic party questioned his ability to remain impartial on the question of preventative detention. He replied that the fact that preventative detention was legally constitutional was a position of his client, not his, even though he happened to give that precise advice as an attorney advising his client of that position.

With then-Associate Justice William H. Rehnquist, Jr. firmly in place, the D.C. Circuit affirmed the constitutionality of the statute in 1981, even though at the time it was sparingly used on fewer than 100 people over the decade.

Then, in 1981, a former advocate and vocal defender of racial segregation, Senator Strom Thurmond,[2]successfully spearheaded as prime sponsor[3] the movement to pass a federal preventative detention statute as part of the Bail Reform Act of 1984, launching a national movement in favor of preventative detention which several states have now copied. Many testified that the statute was unconstitutional, including learned appellate judges, but those arguments ultimately fell on the unpersuadable ears of one of the inventors of preventative detention now sitting behind the bench at the U.S. Supreme Court, newly-minted Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist, Jr., who in no suprise wrote the majority opinion concluding that the preventative detention statute was constitutional. U.S. v. Salerno, 481 U.S. 739 (1987).

Delaware Attorney General Kathy Jennings will now take the torch of preventative detention directly from the hands of Strom Thurmond and Solicitor General Charles Fried and carry their movement directly to the steps of the U.S. Supreme Court. Solicitor General Charles Fried, an early opponent of Roe v. Wade, told the Court at oral argument in 1987 that the “Clockwork Orange” scenario, posited by opposing counsel of a mass incarcerated world, would not come true and that if it did he would not want to live in such a world. It did come true—federal pretrial detention went from 24% to 75% detained, with the average length of detention going from roughly 60 to 360 days.[4] Of what the system the federal system turned into, something Fried promised it wouldn’t, he conceded: “it frightens me as well.”

General Jennings now will go in and present the historical evidence to the U.S. Supreme Court, that the constitutional change was not envisioned by the framers of our constitution, but by instead by a nefarious Richard Nixon in a smoky backroom with a slick attorney who used the federal enclave to create a new idea where the government can just say you are dangerous and that is all. Of course, the house that Rehnquist built was also built on the governments’ settled ability to detain American citizens of Japanese ancestry who were never charged with a crime, the so-called Korematsu case, something the United States Department of Justice and United States Supreme Court, under Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr. recently renounced.

A generation later, Delaware Attorney General Kathy Jennings on behalf of the taxpayers of Delaware will be the next to take the lectern before the U.S. Supreme Court to defend a system that increased federal mass incarceration by nineteen-fold in a generation, was created by advocates of racial segregation who were in the centuries long business of labeling people as “dangerous,” and by a president hell-bent on crushing a movement against his policies by obstructing settled constitutional doctrines like the right to bail.

As Gerald Ford once firmly concluded upon his swearing in as President, “Our long national nightmare is over.” Yet, when it comes to “pretrial preventative detention” policies that came from the same administration that had little respect for the rule of law, that nightmare goes on and will now be inserted into the Delaware constitution.

Delaware Attorney General Kathy Jennings has the power to stop it dead in its tracks; but, instead, she’ll spend Delaware taxpayer dollars to not only defend Strom’s law but to go out publicly and encourage a Democratic majority in the Delaware General Assembly to insert it into Delaware’s constitution for all time.

It appears that General Kathy Jennings will indeed carry Strom Thurmond’s torch of preventative detention for future generations.

[1] https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CHRG-REHNQUIST-POWELL/pdf/GPO-CHRG-REHNQUIST-POWELL.pdf at 78.

[2] “[A]ll the laws of Washington and all the bayonets of the Army cannot force the Negro into our homes, into our schools, our churches and our places of recreation and amusement.” https://segregationinamerica.eji.org/segregationists#full

[3] https://www.congress.gov/bill/98th-congress/senate-bill/215

Facebook Comments